There’s at least one milestone Tiger Woods hasn’t achieved just yet: turning 50. But that’s about to change. On Dec. 30 (today!), Woods hits the half-century mark, an occasion we’re honoring here at GOLF.com by way of nine days of Tiger coverage that will not only pay homage to his staggering career achievements but also look forward to what might be coming next for a transformational player whose impact on the game cannot be measured merely by wins or earnings or even major titles. In our latest “Tiger @ 50” entry (below), Michael Bamberger sizes up Woods’s three life acts.

MORE “TIGER @ 50” COVERAGE: How much is Tiger actually worth to golf? | Will Tiger tee it up on the PGA Tour Champions? | Why Tiger’s 2000 bag still feels untouchable | Explaining Tiger’s famed “gate drill” | Tiger stats you’ve never heard | Was this the end of Woods’s career? | The 1 part of Woods’s legacy we’re waiting to understand | Tiger’s hidden gear hack

***

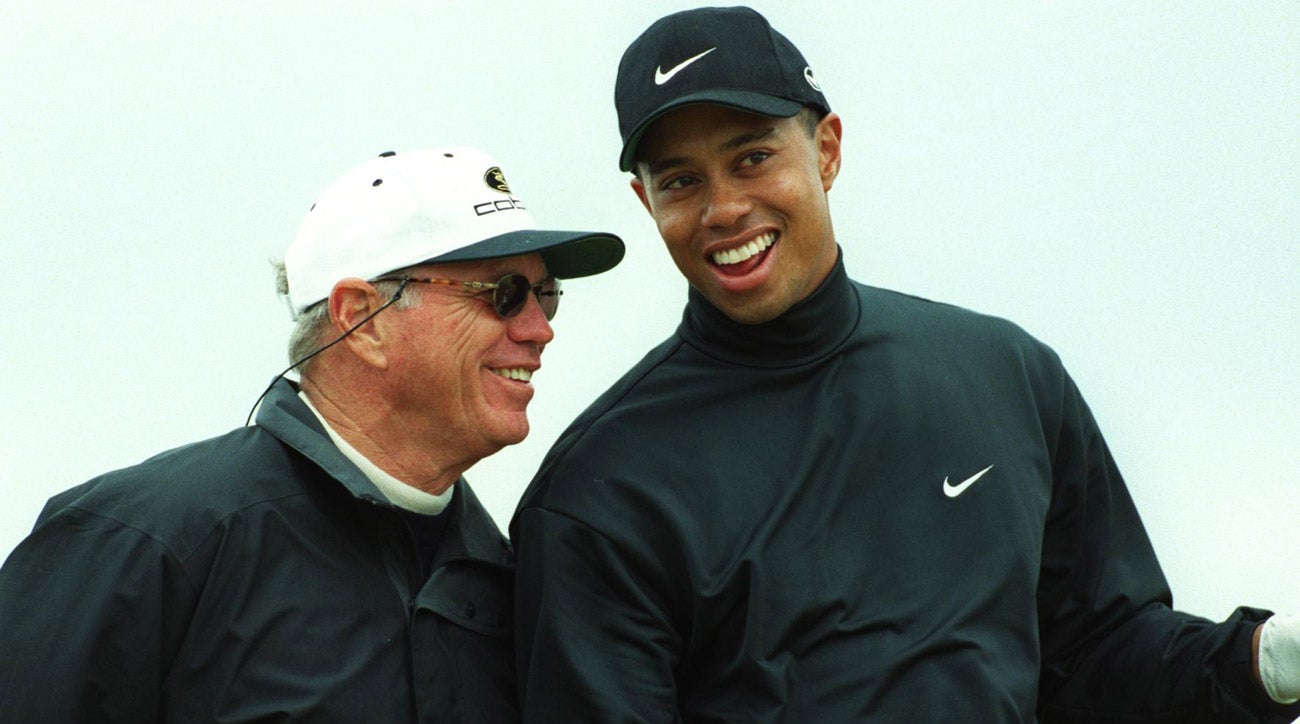

If you have invested any emotion in Tiger Woods, and millions of us have, you know that Butch Harmon plays a major role in the movie that is Tiger’s sui generis life. Harmon was Woods’s swing coach when Tiger was (by far) the best amateur golfer in the world and later when Tiger was (by far) the best professional golfer in the world. Tiger turned 50 on Dec. 30. Butch is 82. You’re whatever you are. Nobody’s getting younger here, though whole industries are devoted to eluding that fact of life. Tiger in the gym is a piece of this. Nothing about his physique hints at middle age. A neat trick and a lot of work. But every year he has a birthday and this year is no exception. He was born in 1975. Jerry Ford was president.

Butch Harmon’s closest friend is a man named Sam Reeves. Anybody who knows Sam — Fred Couples; various coastal caddies; Sam’s wife and their four daughters — will tell you that Sam is an uncommonly insightful person. Tiger has been with Sam, here and there and over the years. Sam played in one U.S. Amateur — and one validating U.S. Senior Am — and can break his age regularly. He’s 91, and he swears by Butch, as swing instructor and man.

When Sam turned 60, newly retired from a long career in the cotton business, he started to see his life in three distinct chapters. His first three decades, he realized, were his preparation years. In his next 30 he was implementing what he had learned in the first 30. Then came 60, 60 on out, and the chance to validate all he had learned, for his own benefit and for those he knew and loved. Validate, and share. Preparation; implementation; validation.

I know, I know: This is getting heavy, here on the eve of New Year’s Eve. I should probably point out that Sam has a mile-wide fun streak. As each of his daughters married, the new sons-in-law got the same tip from Sam: “Go see Butch.” For Sam, as well as for Butch, playfulness is an elemental part of life. Elite players have always liked taking lessons from Butch for his swing insights — and his stories.

In your validation years (as I have processed the concept), you’re sorting through your life experiences while adding to them. You know a thing or two because you’ve seen a thing or two. You’re picking through the pile, looking for keepers, for your own benefit and to benefit others, too.

This timeline is nothing like one-size-fits-all. When you’re talking about a prodigy — a Leonard Bernstein, a Pablo Picasso, a Tiger Woods — timeline adjustments are especially necessary.

Tiger completed his preparation years by 20 and turned pro. (He was 21 when he won his first Masters by 12.) His second act, his implementation years, are impossible to summarize in a tidy way. He was a study in greatness; he was an inspiration; he was a cautionary tale. From 20 to 45, despite long stretches on the IR list, he won like nobody’s won in golf before: 82 PGA Tour wins, 15 of them majors. He implemented, all right. Ask Vijay, Davis, Ernie, Phil. For a long while there, Tiger Woods was implementing like a man on fire. He was 43 when he won his fifth Masters and his 15th major.

You could say that Tiger’s validation years began at age 45, and not at a birthday party. On a still Tuesday morning in February 2021, in a semi-rural section of sprawling Los Angeles County, Tiger Woods, driving alone in a loaner SUV, inexplicably drove across a raised median on a four-lane, 45-mile-per-hour road, across two empty lanes and down a hill, the gas pedal (per the sheriff’s report) virtually floored. The vehicle’s black box recorded his speed at approximately 80 miles an hour until his battleax SUV was stopped by a tree. He was wearing a seat belt and the air bag functioned. Lucky man. He owes his life (in anybody’s telling, including Tiger’s) to the EMTs and medical professionals who tended to him, at the scene and in the coming weeks, along with Tiger’s own will and whatever other grace you may want to add to this harrowing scene.

As a golfer — the golfer we knew — Tiger’s run was over. A body, even his, can withstand only so much. In the 20 majors held since that crash, Woods did not play on 12 occasions, withdrew from two without finishing, missed four cuts and had two near-the-bottom finishes. His play in tournament golf is no longer anything like his highest priority. It can’t be.

But Woods, a single father dating Vanessa Trump, has watched his teenage daughter, Sam, play innumerable minutes of high school soccer. He has watched his teenage son, Charlie, play innumerable shots, in golf tournaments and outside them. He has attended to a thousand details related to Tiger Woods learning centers and various golf courses bearing his stamp, both public and private. He has devoted uncountable hours in an effort to ensure that the sports organization that fueled his childhood dreams and defined his adult life — the follow-the-sun pro golf circuit — has a future that is nearly as rich as its Hogan-Palmer-Nicklaus past. The Tour.

***

WOODS’S VALIDATION YEARS, HIS THIRD ACT, is a work in progress. Two young people, Sam and Charlie Woods, know best the life lessons that come from being Tiger Woods. They know what he shares and why he shares it. Few others could say the same. We all know that Tiger runs private. His choice, of course. Charlie is a junior in high school and Sam a freshman at Stanford, where Tiger went to school for two years. Years ago, Woods told the interviewer Charlie Rose he regretted not staying at Stanford longer. Interesting. Maybe, here on out, he’ll share more.

Woods made the biggest decision of his life in a Los Angeles hospital, late winter ’21, a decision shaped by the core trait of his first 20 years (the preparation years) and the next 25 (the implementation years): He would not quit. If the man stands for any one thing, that’s it. He does not quit. (His cuts-made record serves as testimony.) In mid-March 2021, just after Justin Thomas had won the Players Championship, Erica Herman (then Tiger’s girlfriend) and Joe LaCava (then his underworked caddie) flew to Los Angeles, went to a hospital, collected one of the most famous people in the world and brought him to home to South Florida. Five years ago, almost. His validation years were underway.

And now Tiger’s 50.

A nice round number, and a meaningful one for any tournament golfer with an eye on the Champions tour, the pro circuit for the 50-and-over crowd. A half-decade into his validation years, Tiger Woods unwrapped a birthday gift: by dint of his playing record and his birth certificate, in 2026 he can play in his first Senior PGA Championship, his first U.S. Senior Open, his first Senior British Open, along with any other senior event he decides to play in.

He’s been aware of those three senior majors for years. Woods, a golf-history buff, broadly knows what Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Lee Trevino (to cite three players he genuinely admires) did in them. He knows what his buddy Mark O’Meara was doing, week in and week out, in his 17-year career on the senior tour. Tiger’s admiration for Bernhard Langer, the greatest of all senior players, is not a state secret. When Langer and his son defeated Woods and his son in a playoff at last year’s PNC Championship, Woods said something like, “Bernhard? You’re the best. You’re the best, dude. Awesome.” In defeat! When Woods won the 2019 Masters, the last person he shook hands with before entering the clubhouse and the scorer’s room was Langer. They did not chest bump or engage in a joint primal scream or do any other stupid thing. They shared a few meaningful words and a heartfelt handshake. Just two men who know — craftsman to craftsman, digger to digger, lifer to lifer — how hard it all is. It was beautiful.

The guess here is that Woods will play the three senior majors in 2026 if his body allows him to, and if he can’t, over the next decade he’ll play in as many as he can. Not to pad his record but for a reason far more basic. Tiger Woods is a competitive golfer. Competitive golf is like oxygen to him. Also, his ultimate escape.

He’s not beating Rory and Bryson and Scottie on the world’s hardest courses anymore. But defeating Stewart Cink and Ernie Els and Padraig Harrington on serious courses with handsome hardware waiting in the wings, the trophies bearing the names of legends? Woods will be all in. He once said (again, to Charlie Rose) that winning by one was good “but it’s a lot better if you win by five or six.” Demoralize the competition for next time. That instinct doesn’t just shrivel up and die. As a golfer, Woods was always an assassin.

Hogan was different. Hogan was obsessively looking to perfect the art of striking a golf ball, a grail all its own. Palmer lived for the adulation of strangers, which kept him playing and playing. Woods is most like Nicklaus. Nicklaus needed to compete and Woods needs to compete, probably even more than Big Jack ever did. Competing meaningfully in regular majors is asking too much of Woods. Competing in senior majors is not. If you want to see Tiger Woods playing for keeps, there will be opportunities, and there will be blood. That’s how Tiger rolls. He leaves pools of sweat, and puddles of blood. It was never pretty. Heavyweight title fights never are.

Nicklaus at tournament press conferences, through his 50s, 60s, 70s and into his 80s, has offered repeated opportunities to learn something about golf and really about life. Trevino, the same. You could say both have been taking their validation years seriously, but the more basic thing is that, at some point, you can’t help yourself. You know a thing or two and you want to share. It would be most excellent, to hear Tiger Woods just relax, hang out and . . . pontificate. Maybe that’s coming.

I can’t imagine Woods ever being a Ryder Cup captain. Too many meetings for too little reward. But Tiger as a Walker Cup captain? Especially if Charlie were even remotely in the running to make his team? Yes. Why not? Woods (I think) would relish the chance to lead a group of hot-shot American kids (and Stewart Hagestad) over the course of one intense week at a great course and club. The 2032 Walker Cup is at Oakmont.

***

WHAT ELSE? WHAT ELSE, FOR TIGER, 50 on out? Arnold Palmer had his invitational at his course. Jack Nicklaus has his, at his. Tiger is already the host of the Genesis Invitational, the old and semi-sacred L.A. Open at the old and semi-sacred Riviera Country Club. Tiger will want more. (More is in his DNA.) His tournament on his course. Maybe he’ll buy a piece of Riviera, where he played his first PGA Tour event, as a 16-year-old amateur, an hour by car from his childhood home, traveling predawn before the northbound 405 roared to life. Nicklaus and Palmer created tournaments, courses and clubs in their own images. Woods will want to do the same. Your validation years are loaded with opportunity, in ways both modest and grand.

Like Nicklaus and Palmer, Woods will build courses. He’s built a few already. He has two projects that will be available for all to see and sample in the new year, at the Cobbs Creek golf course in Philadelphia and at The Patch in Augusta, Ga. Each will have a Tiger Woods short course, ideal for beginners, attached to a municipal course where, and this is not a coincidence, Black golfers have left a vital mark. (Charlie Sifford, to cite one prime example at Cobbs; Jim Dent and dozens of Augusta National and Augusta Country Club caddies at The Patch.) There’s already a par-3 course designed by Woods next to the driving range at Pebble Beach. There will be driving ranges at The Patch and Cobbs Creek, too. But also Tiger Woods learning centers, with labs and classrooms and teachers and tutors. Tiger’s father, Earl Woods, was one of 10 kids. He graduated from Kansas State, where he had been an ROTC student and a starting catcher on the baseball team, at 21. (His preparation years were over.) His education changed the course of his life, and Earl Woods preached the benefits of stay-in-school all through his own validation years. He was a piece of work and loaded with insights.

This is from the Tiger Woods Foundation website, and it may read like a boilerplate press release, but it actually packs a lot of punch: “Built on Tiger’s belief in the power of education, the TGR Foundation is making a positive impact on the lives of students from under-resourced communities. We have served more than 217,000 students through our education programs and TGR Learning Labs, providing them with the knowledge, confidence and tools needed to discover their passions and unleash their potential.” The kids here are climbing a ladder leaning on a tree of life. Earl and Tiger would both say that.

Tiger will try to make piles of money, here on out, and maybe he will. Forbes reported this year that Michael Jordan is worth $3.8 billion. It put Woods’s wealth at $1.3 billion. (Those numbers alone, even with their built-in guess work, tell you something about the chasm between basketball as a global sport and golf as its shy cousin on the world’s sporting stage.) A golfer in his validation years who wants to make money has to sell and Woods is trying to sell, even though he’s by no means a natural at it. He has, among other enterprises, a clothing line, Sun Day Red. You want an old-timey glorified windbreaker like the ones baseball managers used to wear at spring training? Tiger will sell you one, for $350. It’s in his 1992 Collection.

That’s the year he played in the L.A. Open for the first time. Fred Couples won that year, in a playoff over Davis Love. Tiger missed the cut. He was still in his preparation years. This was the old Tour, glorified fundraiser car washes featuring Huey Lewis at Wednesday pro-ams and Nick Price on Sunday afternoons. For some decades, starting in the late 1990s, Davis was a sort of tutor for Tiger on the secret handshake of Establishment Golf. Davis and Tiger are all in on the PGA Tour and always have been. Fred, too. Fred and Tiger hang at every opportunity.

Everybody in Tiger’s circle was and is all-in on the Tour. His longtime agent, Mark Steinberg. Tiger’s buddies Rory McIlroy and Justin Thomas. The trainers and physios and instructors in Tiger’s life, they’re all all-Tour, all the time. Woods is on the PGA Tour policy board. He’s the chairman of the Tour’s Future Competition Committee. He’s on the Tour’s Enterprises Board, the for-profit arm of the mothership. You know the Tour’s logo, a white silhouette of a swinging golfer with a Reverse C finish? You can imagine it as the wallpaper theme in his Jupiter Island kitchen. Tiger probably hates that C finish. Bad for the back. But it looked super-cool on Tom Weiskopf. Weiskopf played and Tiger watched. The golf was on ABC or CBS or NBC.

The PGA Tour is one of the true constants in Tiger’s life. He watched it, in person and on TV, all through his preparation years. “Eighty-two PGA Tour wins” is a perfect shorthand summary of his implementation years. All through those 25 years he showed us a level of excellence and domination we had never seen before. We saw the costs of his drive, too. Not in an intimate way, not the way his kids and his mother and his former wife did. But we saw more than enough.

The hydrant thing in 2009; the roadside DUI in 2017; the smashed Genesis SUV in 2021. Various episodes of rulebook weirdness in 2013. (He could have dropped out of the 2013 Masters after signing an incorrect Friday scorecard; he took a drop en route to winning the Players that was, to my eye, off by a football field; at a September tournament in Chicago, in the woods and with no spectators in sight, he should have seen his ball’s slight movement as he attempted to move a twig. Slugger White had to call the penalty when Woods would not call it on himself.) For a long stretch there, I saw Tiger Woods as a desperate man. I wondered about the underlying issue behind his chip yips in 2014 and 2015. He’s had some tough times on the road to 50. Who among us, done pushing 50, would not say the same? Scottie Scheffler has 21 years to go. A lot will happen. He’s in the early stages of implementation, his Act II.

***

AND HERE’S TIGER IN ACT III, with a new benefit just coming online, the standing invitation to play senior tour golf. Other than that, 50 is not the milestone that the birthday-card industry would have you believe. “50 IS THE NEW 40!” Nope. This is older and truer: 40 is the old age of youth; 50 is the youth of old age. That’s Victor Hugo, 19th-century French writer, who lived to the ripe age of 83. Ben Hogan, 20th-century American golfer, made it to 84. Given the many unfiltered Chesterfields he smoked, the many adult beverages he drank and the one demon Greyhound bus that plowed into his Cadillac, Hogan led a surprisingly long life. He died in 1997. All these years later, Hogan still looms over golf and informs any serious consideration of the life and times of Tiger Woods. (The dirt, the dirt, the dirt.) Butch Harmon will tell you that Greg Norman was the hardest-working golfer he ever taught and the best golfer he ever taught until Tiger came around and blew by Norman in both categories.

Maybe you were around for those few thrilling seconds when Tiger played that pitch shot from over the 16th green, Sunday at Augusta, at the 2005 Masters. Those few seconds when his Nike golf ball trickled on down the green’s famous slope, bound for the hole for several seconds before sitting on the lip for an eyeblink until the inky weight of its logo gave it the final nudge it needed to go four inches under. For a long, delicious moment there, nobody could breathe. Not Tiger, not Stevie beside him. Not Tiger’s playing partner and opponent, Chris DiMarco. Not Verne, in the booth. Not you, not I. Tiger was 30. Every single eye was on one of two things, there at 16: Tiger’s ball, or Tiger his own self. For Tiger Woods, the artist who created that moment, nothing again will ever be that intense, that exciting, that everything. Not in his golfing life. That’s OK. That’s how it goes: X moves out, Y moves in, the beat goes on.

Happy birthday, Tiger. Here’s to your future. Pack shades. You’re gonna need ’em.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com.

The post Tiger Woods has lived his first two acts. His third act is a work in progress appeared first on Golf.