As a student at Stanford is a Cardinal, an intern at the United States Golf Association is a Boatwright. At any given time, there are several hundred Boatwrights, working at the USGA or in one of golf’s many regional administrative organizations — your Idaho Golf Association, your Golf Association of Philadelphia, your Sun Country Golf Association, covering West Texas and New Mexico, scores of others. There are thousands of alumni Boatwrights. Many Boatwrights hold year-long positions. For others, the positions are June-July-August gigs, timed to the academic calendar. As summer starts its long and mournful farewell here, scores of Boatwrights are going back to school, or looking to start careers, often in golf.

Which brings us to Alegra Gurian of Pacific Palisades, Calif., who got bitten by the golf bug late in her high school years. She had been a drummer and a musician. Then golf did what golf does: It took root. After graduating from Palisades Charter High School in 2016, Alegra worked in outside services at the tony Brentwood Country Club for a year. She then went to Sonoma State, read a lot of Russian literature and over time got her handicap down to scratch or better. This summer she worked for the Southern California Golf Association, as a Boatwright. She’ll be a Boatwright for life.

The Boatwrights see the game from the ground up. They do the things we all take for granted. You know those just-the-facts emails you get from your local golf association about changes in the handicap system? Or how you show up at a golf association tournament and your scorecard is marked up and ready to go, and the ground-under-repair is marked, too? Well, somewhere in all of that there could be an Alegra Gurian, doing her thing. Or, if your golfing life is under the purview of the SCGA, the actual Alegra Gurian.

“I took up golf for the P.E. credit,” Alegra, now 27, said in a phone interview the other day. Golf took over. At Brentwood, she got a taste of real-world golf. Part of the job was to load golf bags from car trunks to golf carts and secure them in place with those airline-style safety belts. “Brentwood has a no-tipping policy, and this guy left a 20 for me,” Alegra said. “I ran after him and said, ‘You forgot this.’ He gave me this look, like, Huh?” It was probably right around then that it became obvious: She had what it takes to be a Boatwright. She had the stuff!

Boatwright, Boatwright, Boatwright. You can visit the USGA website, most anytime of year but particularly in midwinter, and the whole program, with all of its openings, is laid out. As for the man behind the name, there was once a P.J. Boatwright, and there are still loads of golfers around who remember the man well. He was a legendary USGA executive, a course set-up man and rules official, who joined the USGA in the late 1959 and staying with the organization until his death, by cancer, in 1991, at age 61. The very mention of the name, Boatwright’s daughter-in-law, Cathy Boatwright, a rules official herself, will tell you, can still bring tremors of fear to players who crossed paths with him.

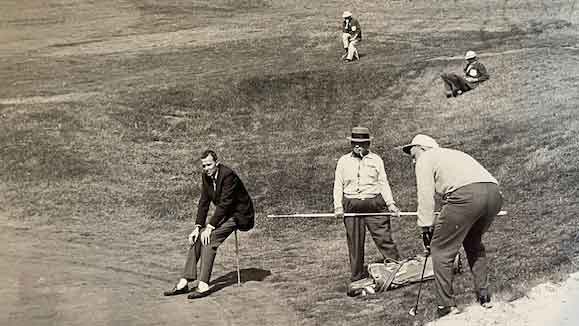

In the second round of the 1990 Masters, my friend Mike Donald hit a tee shot on 18 that went dead left, bounced off the roof of a restroom and disappeared into a cement flood-control drain. Mike called for an official. P.J. showed up in a cart, likely wearing his everyday I-mean-business uniform, a white button-front shirt, a striped tie, a USGA blazer. David Eger, a much younger rules official, was riding shotgun, almost like an apprentice learning from the master. Boatwright declared that Mike’s ball was now in a hazard — penalty area in today’s parlance — no different from being in a pond.

“A hazard?” Mike said. “How the f— can it be a hazard? It’s not even marked!”

You can imagine how moved Pervis James Boatwright Jr., native Augustan raised in South Carolina, was by that argument. Without breaking a sweat, he laid out Donald’s simple options: take a drop near the drain with a one-shot penalty, or play 3 off the tee. There was no appeals process. Boatwright was the highest court in the land.

Curtis Strange, Hollis Stacy, Brad Faxon, Corey Pavin, Nancy Lopez, innumerable others can tell P.J. stories.

There’s a plaque at the old USGA headquarters in New Jersey that reads thusly:

P.J. Boatwright served the USGA with dedication and distinction for over three decades.

Renowned for his expertise in conducting championships, he was also the world’s foremost authority on the rules of golf.

P.J. was the ultimate arbiter in maintaining the integrity of the game, and his influence will be felt forever.

The author of those sentences likely did not have the Boatwright Internship Program in mind when writing those last six words, but they are no doubt true. As the man’s namesake son, P.J. Boatwright 3d, said in an interview the other day, it’s only a matter of time until there is a USGA CEO who is a former Boatwright intern. Thomas Pagel, the USGA’s chief governance officer, is a Boatwright alum. So is Emily Palmer, a Boatwright in 2003 who is now the USGA’s chief member service officer.

Palmer can still recall her Boatwright indoctrination, the gathering of Boatwright interns from all over the country at Golf House, the old estate-like USGA headquarters in bucolic Liberty Corner, N.J. That orientation is now called the Boatwright Summit and Palmer described it recently as a “deep dive” into the USGA’s core values and a crash-course into the services the USGA provides.

The public, and many elite golfers, sometimes to not seem to grasp the USGA’s essential mission, to make golf a better game for more people. The USGA is much closer to a great, independent public research university than a business. It’s not a business at all, not in the conventional sense. It has no profit motive. It invests in the game.

The USGA has poured $35 million into the Boatwright Internship Program over the past 34 years. Some of the internship positions pay on the order of $20 an hour. Others offer a $2,000 per month stipend. All of them come with ample opportunity to play golf, be around golf, attend national golf championships. The positions give the interns a chance to learn the administrative side of the game from the ground up. Janeen Driscoll, the USGA’s director of brand communications, noted recently that one-third of all executive directors of state and local golf associations were once Boatwrights. She knows Boatwright stats like a baseball junkie might know slugging percentage numbers over both leagues. Driscoll notes that, in 2025, there was a Boatwright as young as 18 and as old as 68.

The hits just keep coming: In Boatwright’s day, the USGA was pretty much a men-only operation, and so were the state golf associations. That was then. Of the 215 former Boatwrights hired by golf associations this year, about 40 percent were female.

Over the years, golf administration in the United States has been overwhelmingly white. So has the Boatwright program — 15 percent of the current interns identity themselves as people of color.

Four years ago, to raise that number and to make American golf administration more representative of American golf, the USGA began a pathway program to the internship program, aimed at university students of color with an interest in golf. This year, at the U.S. Open at Oakmont and in the days leading up to it, there were 25 young people of color getting a 10-day golfing baptism by fire. The USGA — the modern USGA — values diversity. The current USGA president, Fred Perpall, is a Black construction executive in Dallas who grew up in a working-class family in the Bahamas where they talked about golf about as often as they talked about snow.

Boatwright was a good amateur golfer who made the cut in the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion. He knew Ben Hogan. He also knew Joe Dey, the rules expert and golfing ethicist who was the USGA’s first executive director, from 1934 to 1968. He received letters from Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, when they learned of Boatwright‘s cancer diagnosis. He was awarded an engraved silver plate for being the runner-up in the sixth flight of a hoity-toity amateur event at the Biltmore Forest Country Club in Asheville, N.C. Even then it was a vanishing world. What Boatwright was most committed to was the values of the game, “winning with humility and losing with grace,” as his namesake son said recently.

PJ3 is certain his father would be stunned and thrilled to see the scope and diversity of the thriving internship program that bears the family name. “Dad would recognize that everything has to change,” Boatwright, a retired Time Inc. executive, said the other day. The game could have stayed stagnant and small. But in the years since World War II, American golf has exploded, and the USGA has, too. What would make the PJ1 ill is the pace of play, Cathy Boatwright said.

Most years, in mid-May, P.J. Boatwright 3d makes the 2.5-hour drive from his home in Fairfield, Conn., to Golf House in the Garden State horse country to speak at a dinner to the assembled Boatwrights at their orientation, the Boatwright Summit. Two-hundred or more interns, gathered under a tent, each of them, in a manner of speaking, flying the Boatwright flag. The son shares with them one of the lessons he got from his father: “Don’t focus on what anybody else is doing. Focus on what you can do.” Words to live by.

With her Boatwright internship all wrapped up, Alegra Gurian is trying to figure out what she can do in the game. For now, she is an instructor in the Southern California Golf Association, bringing the game to new golfers, the way her gym teacher at Pali High once did. She loves it. Her here-and-now is golf. Her tomorrow is golf. She kind of knew that before she began her stint as a Boatwright. Now she’s surer yet. She’s a Boatwright. You know what they say: Once a Boatwright, always a Boatwright.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com

The post Want to work in golf? This immersive internship program is a good place to start appeared first on Golf.